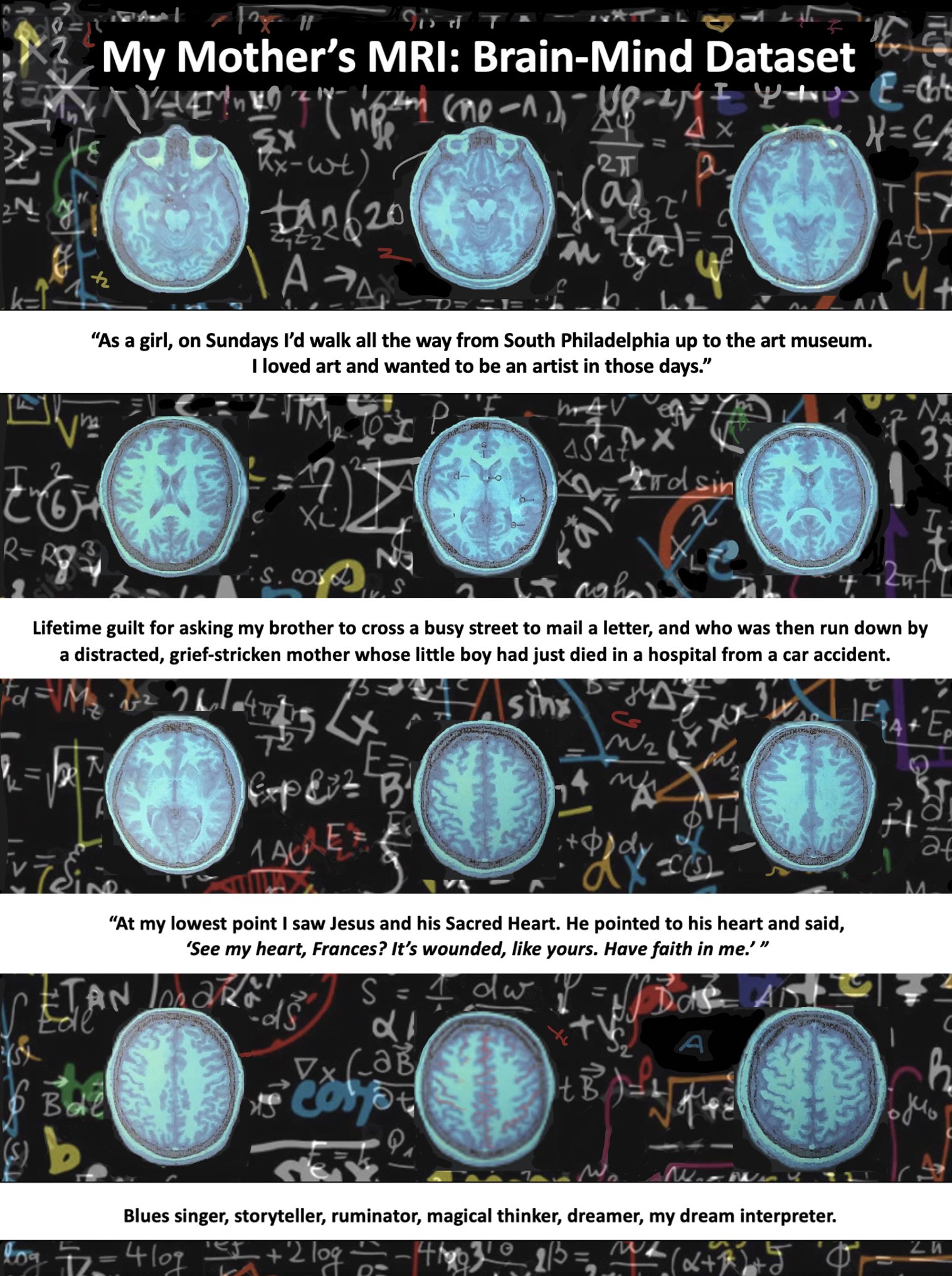

My mother Frances had a life shaped by sorrow. Her mother died when she was just eight, a loss too large for such a small girl. On her sixteenth birthday, she learned that the man she called father was not her biological one. That revelation split her world in two.

She became a wartime bride, but married my father on the rebound—her heart still tied to another. She never truly settled into the life she ended up with. One afternoon, she asked my older brother Frank to mail a letter across the busy street near our home. A car struck him. The driver was a grieving woman whose own son had just died in a nearby hospital. Frank’s injuries disfigured his face and required multiple surgeries. My mother never forgave herself. And he never recovered emotionally. She died at fifty-one from lung cancer. He followed at thirty-one, a sudden heart attack silencing him forever.

— Tony Errichetti

Despite all this, my mother was a storyteller. From the earliest days, I was her audience. She’d sip coffee, chain-smoke Chesterfields, and talk as if the act itself might keep the grief at bay. And I listened. Her stories were not just entertainment—they were survival, and they taught me to listen with care, a skill that would shape my life as a therapist.

She had a wry, stubborn sense of humor. She could laugh through the wreckage. Once, she told me, “Jesus must have made people laugh, or else no one would’ve followed him. We need a sense of humor to get through life.” I never forgot that.

But perhaps her greatest gift was curiosity—hers and the one she instilled in me. She listened to my dreams and childhood nightmares, offering interpretations. She bought me books and never questioned my hunger to know more. That was her quiet way of giving me a future beyond her own pain.